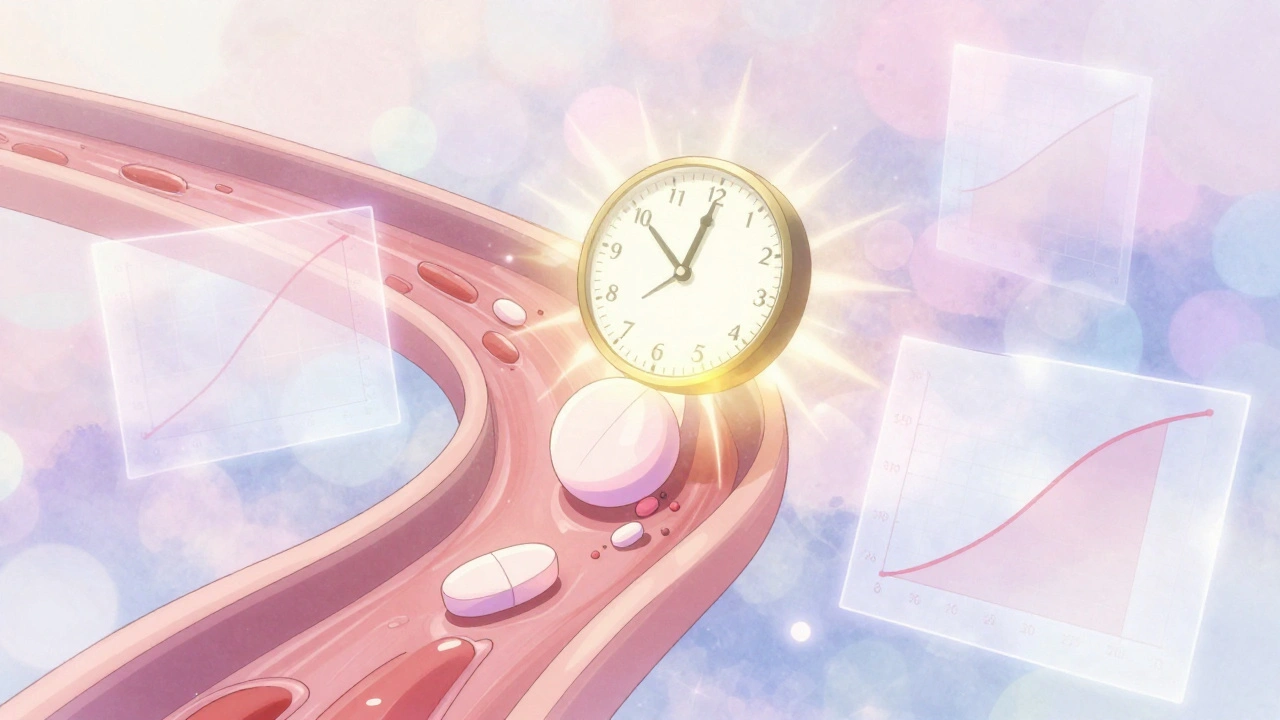

When a generic drug hits the market, it’s not enough for it to contain the same active ingredient as the brand-name version. It must behave the same way in the body. That’s where bioequivalence testing comes in. For years, regulators relied on two simple metrics: Cmax (the highest concentration in the blood) and total AUC (the total drug exposure over time). But for complex drug formulations - especially extended-release pills, abuse-deterrent opioids, or combination products - those metrics often missed the real story. Enter partial AUC, or pAUC: a more precise, targeted way to measure how a drug is absorbed in the critical early hours after dosing.

Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short

Imagine two painkillers. One releases its drug slowly over 12 hours. The other releases the same amount quickly, then tapers off. Both might have identical Cmax and total AUC. But if the fast-release version spikes too early, it could be abused. Or if the slow-release version doesn’t reach effective levels fast enough, patients won’t get relief when they need it. Traditional bioequivalence tests can’t catch those differences. They treat the whole curve like a single number - ignoring when and how the drug gets absorbed.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2014, a study in the European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences found that 20% of generic drugs that passed standard bioequivalence tests failed when pAUC was applied. When researchers looked at both fasting and fed conditions together, failure rates jumped to 40%. That means nearly half of the generics approved under old rules might not have worked the same way in real patients.

What Is Partial AUC?

Partial AUC measures drug exposure only during a specific window of time - not the entire curve. Think of it like zooming in on the first 1, 2, or 4 hours after a pill is taken. That’s when absorption matters most. For extended-release products, the early phase determines whether the drug kicks in fast enough. For abuse-deterrent formulations, it ensures the drug doesn’t release too quickly if someone crushes the pill.

The FDA and EMA both now recommend pAUC for certain products. The EMA first introduced it in a 2013 draft guideline targeting prolonged-release formulations. The FDA followed, especially after a 2017 workshop where they called pAUC an “improved metric” that’s sensitive to differences in high-concentration regions of the curve - and less affected by noise in low-concentration zones. In plain terms: it focuses on what’s clinically meaningful.

How Is pAUC Calculated?

There’s no single formula. The time window depends on the drug and its intended use. Common approaches include:

- From time zero to the time when the reference product reaches its peak concentration (Tmax)

- From time zero to 50% of the reference product’s Cmax

- From time zero until drug concentrations drop below a certain threshold

For example, if a reference painkiller peaks at 3 hours, a pAUC might be calculated from 0 to 3 hours. If the test product shows significantly lower exposure in that window, even if total AUC matches, it’s not bioequivalent. That’s the power of pAUC: it isolates the absorption phase.

Statistically, pAUC data is log-transformed and analyzed using the same 80-125% confidence interval rule as traditional metrics. But because pAUC often has higher variability - especially when Tmax differs between subjects - studies may need larger sample sizes. One industry survey found that pAUC studies often require 25-40% more participants than standard ones.

Where Is pAUC Used Today?

pAUC isn’t used for every drug. It’s reserved for complex formulations where timing matters. According to FDA data from 2022, the highest use is in:

- Central nervous system drugs (68% of new submissions)

- Pain management products (62%)

- Cardiovascular agents (45%)

Abuse-deterrent opioids are a major driver. The FDA now requires pAUC for nearly all extended-release opioids to ensure that crushing or dissolving the pill doesn’t lead to dangerous spikes in blood levels. In one case presented at the 2021 AAPS meeting, pAUC revealed a 22% difference in early exposure between a test product and the brand-name drug - a difference traditional metrics completely missed. That generic was pulled before it reached patients.

By 2022, 35% of new generic drug applications included pAUC - up from just 5% in 2015. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance adds 41 more products to the list, bringing the total to 127 drugs that now require pAUC analysis.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite its advantages, pAUC isn’t easy to implement.

First, there’s inconsistency. FDA product-specific guidances vary widely. Only 42% clearly define how to choose the time window. One company might use Tmax, another might use 50% of Cmax. This creates confusion during study design. In 2022, 17 ANDA submissions were rejected by the FDA solely because of incorrect pAUC time intervals.

Second, it’s expensive. A senior biostatistician at Teva reported that switching to pAUC for an extended-release opioid generic increased their study size from 36 to 50 subjects - adding $350,000 to development costs. Smaller companies often outsource this work to specialized CROs, which now make up 18% of the complex generic testing market.

Third, expertise is scarce. Only 87% of job postings for bioequivalence specialists now list pAUC as a required skill. Biostatisticians typically need 3-6 months of extra training to use it correctly. Tools like Phoenix WinNonlin and NONMEM are essential. Without them, even the best data can be misanalyzed.

The Future of pAUC

The trend is clear: pAUC is becoming standard for complex drugs. Evaluate Pharma predicts that by 2027, 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC - nearly double the 2022 rate.

The FDA is working to fix the inconsistencies. In early 2023, they launched a pilot program using machine learning to automatically determine optimal pAUC time windows based on reference product data. This could reduce subjectivity and improve reproducibility.

But global alignment is still lagging. The IQ Consortium found that inconsistent pAUC rules across the U.S., Europe, and other regions add 12-18 months to global drug development timelines. Until regulators agree on standards, companies will keep paying more and waiting longer.

What This Means for Patients

At first glance, pAUC sounds like a technical detail only pharmacists and regulators care about. But it’s not. It’s about safety and effectiveness.

Without pAUC, a generic painkiller might seem “equivalent” on paper - but if it releases too fast, it could lead to overdose. If it releases too slow, it might not control pain at all. pAUC closes those gaps. It ensures that when you take a generic, you’re getting the same performance, not just the same chemical.

For patients on chronic medications - especially for conditions like epilepsy, depression, or chronic pain - that consistency matters. A small shift in absorption can mean the difference between control and crisis.

pAUC isn’t perfect. It’s complex, costly, and still evolving. But it’s necessary. As drug formulations get more sophisticated, so must the tools we use to test them. pAUC is one of the most important advances in bioequivalence in the last 20 years - and it’s only getting more important.

What is the difference between total AUC and partial AUC?

Total AUC measures the entire drug exposure from the moment the drug enters the bloodstream until it’s completely cleared. Partial AUC (pAUC) only measures exposure during a specific, clinically relevant time window - like the first 2 or 4 hours after dosing. While total AUC tells you how much drug was absorbed overall, pAUC tells you how quickly and effectively it was absorbed when it matters most - such as during the initial absorption phase.

When is partial AUC required by regulators?

Regulators like the FDA and EMA require pAUC for complex drug formulations where traditional metrics (Cmax and total AUC) can’t reliably show therapeutic equivalence. This includes extended-release products, abuse-deterrent opioids, and combination immediate- and extended-release formulations. As of 2023, the FDA mandates pAUC for 127 specific drug products, with more being added each year.

How is the time window for partial AUC chosen?

The time window should be based on clinically relevant pharmacodynamic effects - not just convenience. Common methods include using the reference product’s Tmax (time to peak concentration), the time when concentration reaches 50% of Cmax, or a fixed interval like 0-3 hours. The FDA recommends linking the window to a known clinical effect, such as pain relief onset or seizure control. However, inconsistency in guidance documents makes this challenging for developers.

Does partial AUC increase the cost of generic drug development?

Yes. Because pAUC often has higher variability than total AUC, studies typically need larger sample sizes - sometimes 25-40% more participants. This increases costs by hundreds of thousands of dollars. For example, one generic opioid study saw its budget rise by $350,000 after switching to pAUC. Smaller companies often outsource analysis to specialized contract research organizations (CROs) to manage the complexity.

Can partial AUC prevent unsafe generics from reaching the market?

Absolutely. In a 2021 case study presented to the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists, pAUC detected a 22% difference in early drug exposure between a test product and the brand-name drug - a difference traditional metrics completely missed. The generic was withdrawn before approval, preventing a potentially unsafe product from reaching patients. This is one of the key reasons regulators now rely on pAUC for high-risk drugs.

Wow, this is actually one of those posts that makes you realize how much goes into something you just pick up at the pharmacy.

It's frankly absurd that regulators still rely on outdated metrics like total AUC for anything beyond basic immediate-release formulations. The fact that 40% of generics failed under pAUC testing in 2014 isn't a bug-it's a feature of systemic negligence. The FDA only acted after the opioid crisis exposed how dangerous this complacency was. If you're still using Cmax and total AUC as your primary metrics, you're not a scientist-you're a relic.

Interesting how the UK’s MHRA still hasn't fully aligned with the FDA’s pAUC standards. It’s causing real delays for UK-based generics trying to enter the US market. We’re seeing a lot of companies just skip the UK and go straight to the US or EU now.

I work in clinical trials and we just switched to pAUC for our last extended-release study. The extra cost was brutal, but honestly? Worth it. We caught a 19% early exposure difference that would’ve been invisible otherwise. Patient safety isn’t optional.

Let’s be real-this is just another way for big pharma and CROs to milk the system. They’re creating artificial complexity so they can charge more. If the drug has the same active ingredient, why does it matter if it peaks 30 minutes earlier? Patients don’t care about the curve, they care if it works. This is regulatory theater.

Every time I hear about another $350k study because of pAUC, I think about the patients who can’t afford the brand anymore. This isn’t science-it’s a profit engine disguised as safety. They’re not protecting us, they’re protecting margins. And now they’re forcing small companies out of the market. This isn’t progress, it’s consolidation.

It is a moral imperative that bioequivalence standards evolve in lockstep with pharmaceutical innovation. To continue relying on archaic, aggregate metrics is not merely scientifically indefensible-it is ethically negligent. The patient’s right to therapeutic predictability supersedes corporate convenience. The FDA’s 2023 guidance, while imperfect, represents the bare minimum of ethical responsibility in pharmacovigilance.

17 ANDA rejections over pAUC time windows? That’s not ‘guidance,’ that’s a bureaucratic dumpster fire. The FDA is playing god with arbitrary time intervals while companies waste millions guessing what the next reviewer will want. This isn’t science-it’s a lottery where the house always wins. And the patients? They’re the ones paying with their lives.

Just wanted to say I really appreciate how detailed this is. I’m a med student and this actually helped me understand why some generics feel different even when they’re ‘the same.’ Never thought about how timing affects pain control or seizure risk. Thanks for breaking it down.

Big +1 to Chase. I’ve seen this firsthand with a patient on a generic seizure med-switched brands, had a breakthrough seizure. Turned out the pAUC window was off by 30 mins. Scary stuff. Glad we’re moving toward precision, even if it’s messy.

More money for labs, less for patients. Capitalism wins again.

Wait-so you’re telling me we’ve been approving generics based on ‘total exposure’ while ignoring when the drug actually kicks in? That’s like saying two cars are ‘equivalent’ because they both go 60 mph over 100 miles… even if one takes 30 minutes to get there and the other sprints the first mile then naps for an hour. This isn’t bioequivalence-it’s a cosmic joke.