When opioids stop working-and pain gets worse-you might think the answer is more pills. But what if the medicine itself is making the pain worse? That’s the reality of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), a hidden problem affecting 2-15% of people on long-term opioid therapy. It’s not tolerance. It’s not disease progression. It’s your nervous system becoming hypersensitive because of the very drugs meant to ease your pain.

What Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Actually Feels Like

OIH doesn’t show up as a single symptom. It creeps in slowly. You start with back pain, then your legs start hurting too-even though your MRI hasn’t changed. You’re on 60 mg of oxycodone a day, and now you need 120 mg. But instead of relief, your skin feels raw. A light touch from your shirt hurts. Cold air stings. You’re not getting more pain from your original injury-you’re feeling pain where there never was any before.

This isn’t rare. In clinical practice, it’s often mistaken for tolerance. But here’s the difference: with tolerance, you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. With OIH, higher doses make the pain spread and intensify. Patients describe it as their whole body becoming a nerve ending. It’s called allodynia-pain from things that shouldn’t hurt. A hug feels like needles. Walking on tile feels like stepping on glass.

It usually shows up after 2-8 weeks of steady opioid use, especially with high doses-like more than 300 mg of morphine daily-or in people with kidney problems, where opioid metabolites build up. The pain doesn’t follow your original injury pattern anymore. It’s everywhere. And it gets worse when you take more opioids.

Why This Happens: The Science Behind the Pain

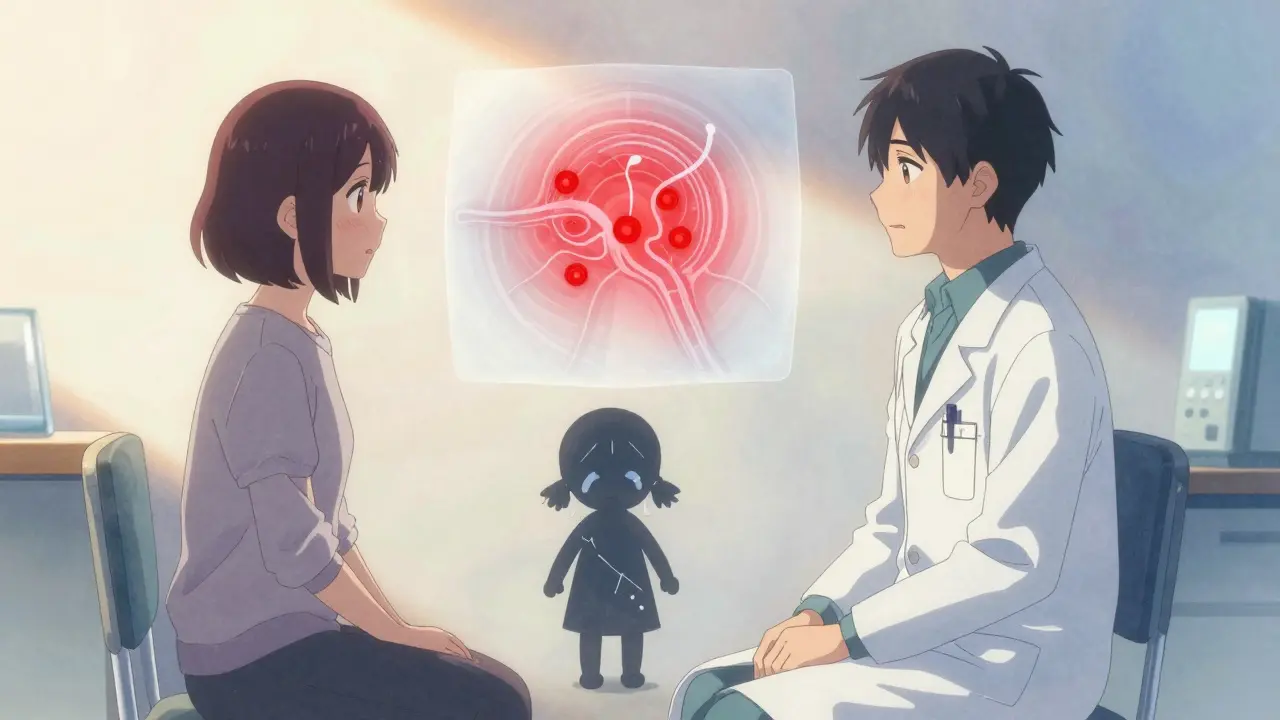

Your body doesn’t just adapt to opioids-it fights back. Opioids bind to receptors in your brain and spinal cord to block pain signals. But over time, they trigger a cascade of changes that do the opposite. The most studied mechanism involves the NMDA receptor, a key player in how your nervous system learns to feel pain. Opioids accidentally turn this system on, making your nerves more sensitive, not less.

Think of it like a volume knob stuck on max. Your spinal cord starts amplifying every signal, even harmless ones. At the same time, your body produces more dynorphin-a natural pain enhancer-and less of the chemicals that calm nerves down. Genetic factors also play a role. People with certain variations in the COMT gene (which affects how your body breaks down stress chemicals) are more likely to develop OIH.

Some opioid metabolites, like morphine-3-glucuronide, are toxic to nerve cells and directly stimulate pain pathways. That’s why switching from morphine to methadone or buprenorphine often helps-these drugs don’t produce the same harmful byproducts. Methadone, in particular, also blocks NMDA receptors, which is why it’s one of the most effective switches for OIH.

Differentiating OIH from Tolerance and Withdrawal

This is where things get tricky. Tolerance, withdrawal, and OIH can look almost identical. All three can cause increased pain and higher opioid needs. But here’s how to tell them apart:

- Tolerance: Pain stays in the same place. You need more opioid to get the same relief, but if you stop, the pain doesn’t get worse-it just returns to baseline.

- Withdrawal: Comes with physical signs: sweating, nausea, anxiety, diarrhea, insomnia. Pain improves when you take your next dose.

- OIH: Pain spreads. It becomes diffuse. It gets worse with more opioids. No withdrawal symptoms. Pain doesn’t improve with the next dose-it gets worse.

One clue? Try a small dose reduction. If pain improves within a few days, it’s likely OIH. If pain spikes and you feel sick, it’s probably withdrawal. If nothing changes, it might be disease progression.

Doctors use tools like the Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ), which asks about pain spreading, sensitivity to touch, and whether pain worsens with dose increases. Studies show it’s 85% accurate at spotting OIH. But even with tools, diagnosis is still a process of elimination. You have to rule out infection, new injury, cancer progression, or nerve damage first.

How to Treat Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia

The worst thing you can do is keep increasing the opioid dose. That’s like pouring gasoline on a fire. The real fix is to reverse the nervous system’s oversensitization.

1. Reduce the dose. Start by lowering your opioid by 10-25% every 2-3 days. Don’t cut too fast-this isn’t withdrawal, but your body still needs time to recalibrate. Many patients see improvement within 1-2 weeks. Full recovery can take 4-8 weeks.

2. Switch opioids. If reducing doesn’t help, switch to an opioid that doesn’t trigger the same pathways. Methadone and buprenorphine are top choices. Methadone blocks NMDA receptors. Buprenorphine has a ceiling effect-it doesn’t keep pushing your nervous system into overdrive like morphine or oxycodone. Avoid high-dose hydromorphone or fentanyl patches if OIH is suspected.

3. Add NMDA blockers. Ketamine, given as a low-dose IV infusion (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour), can reset pain sensitivity in days. It’s not a cure-all, but for severe OIH, it’s one of the few things that works fast. Oral ketamine or dextromethorphan (an OTC cough suppressant with NMDA-blocking properties) are being studied as cheaper, longer-term options.

4. Use adjuvant meds. Gabapentin (300-1800 mg three times daily) and pregabalin calm overactive nerves. Clonidine (0.1-0.3 mg twice daily) reduces sympathetic overdrive. These aren’t painkillers-they’re nerve stabilizers. They work well with lower opioid doses.

5. Non-drug support. Physical therapy helps retrain movement without fear. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses the brain’s role in pain amplification. Mindfulness and graded exposure reduce hypervigilance to pain signals. These aren’t optional extras-they’re essential parts of recovery.

What Happens When You Don’t Address It

Left unchecked, OIH can spiral. Patients get caught in a loop: more pain → more opioids → worse pain → more opioids. Doses climb into dangerous territory. Side effects multiply: constipation, sedation, respiratory depression. Some end up on 500 mg of morphine daily, still in agony.

And it’s not just physical. The emotional toll is heavy. Patients feel betrayed by their doctors. They think they’re weak for not responding to treatment. They’re told they’re “drug-seeking” when they’re just in real, worsening pain. This leads to depression, isolation, and loss of trust in the medical system.

Worse, many end up on long-term high-dose opioids unnecessarily. The CDC found that 10.1 million Americans were on long-term opioids in 2023. If even 5% of them have OIH, that’s over half a million people being treated the wrong way.

What’s Changing in 2026

OIH is no longer a fringe concept. In 2022, the FDA required opioid labels to include OIH as a known risk. By 2024, 65% of pain specialists routinely screen for it-up from 30% in 2010. Pain fellowships now teach it as standard. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has 3 full pages of guidelines on recognizing and managing it.

Research is accelerating. A major NIH study (NCT05217891) is tracking genetic markers to predict who’s at risk. Two commercial genetic tests for COMT variants are launching in mid-2025. Imagine a simple blood test before starting opioids that tells you: “You’re genetically prone to OIH. We’ll start you on buprenorphine instead.” That’s the future.

Pharmaceutical companies are pouring money into it. OIH-specific drug development is up 27% year-over-year. Three new NMDA modulators are in late-stage trials. This isn’t just about better pain control-it’s about fixing a broken system.

What You Should Do Now

If you’re on opioids and your pain is getting worse:

- Don’t assume you need more. Ask your doctor: “Could this be OIH?”

- Track your pain: Where is it? How intense? Does it spread? Does it get worse after a dose?

- Ask about the OIHQ questionnaire-it’s quick and free.

- Request a trial reduction: Can we lower my dose by 20% for 2 weeks and see what happens?

- Ask about alternatives: Methadone? Gabapentin? Physical therapy?

It’s not about quitting opioids. It’s about using them smarter. Many people who switch off high-dose morphine or oxycodone and into a lower, more targeted regimen find their pain actually improves. Their lives get back.

OIH isn’t a failure. It’s a signal. Your body is telling you something’s wrong-not with your pain, but with the treatment. Listen to it.

Can opioid-induced hyperalgesia happen with low-dose opioids?

Yes, though it’s less common. OIH is more likely with high doses (over 300 mg morphine daily) or long-term use, but cases have been reported at lower doses-especially in people with kidney problems, genetic risks, or those using opioids for more than 6 months. It’s not about the dose alone-it’s about how your nervous system responds over time.

Is OIH the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a physiological change in pain processing. Someone with OIH may not crave opioids-they just feel more pain and think they need more. They’re not addicted; their nerves are misfiring. Mistaking OIH for addiction leads to harmful stigma and poor care.

How long does it take to recover from OIH?

Most people see improvement in 2-4 weeks after reducing opioids or switching medications. Full recovery-where pain returns to baseline and sensitivity normalizes-usually takes 4-8 weeks. In some cases, especially with long-term high-dose use, it can take 3-6 months. Patience and consistent treatment are key.

Can ketamine be taken orally for OIH?

Yes, but it’s not as reliable as IV. Oral ketamine and dextromethorphan (found in some cough syrups) are being studied for long-term use. They work more slowly and less predictably than IV infusions, but they’re safer for home use. Doses are carefully controlled-usually 10-30 mg of ketamine daily or 60-120 mg of dextromethorphan. Always under medical supervision.

Will I be in more pain when I reduce my opioids?

You might feel some discomfort as your body adjusts, but it’s not the same as withdrawal. With OIH, the goal is to reduce the pain amplification caused by opioids. Many patients report that after the first week, their pain becomes less intense, less widespread, and easier to manage-even with lower opioid doses. The initial dip is temporary. The long-term gain is real.

Are there any new drugs specifically for OIH?

Not yet approved, but three drugs targeting NMDA receptors and spinal dynorphin are in Phase II/III trials as of 2024. One is a modified ketamine analog with fewer side effects. Another blocks a specific protein linked to pain sensitization. These aren’t just painkillers-they’re designed to reverse the nerve changes caused by opioids. They’re expected to be available by 2027-2028.

OMG I’ve been living this. Thought I was just getting worse at handling pain, but after cutting my oxycodone by 30%, my skin stopped feeling like it was wrapped in barbed wire. Now I can wear a t-shirt without crying. This isn’t weakness-it’s your body screaming for help. You’re not broken. Your nervous system just got hijacked.

Ugh. Another ‘opioids are evil’ thinkpiece. Let’s be real-most people on long-term opioids aren’t suffering from OIH, they’re just addicted and don’t want to admit it. The ‘pain spreads’ narrative is convenient for people who want to blame the medicine instead of their own lifestyle. And don’t even get me started on ketamine infusions costing $2,000 a pop. Who’s paying for this fantasy?

It is both fascinating and deeply tragic to observe how medical science, in its pursuit of alleviating suffering, has inadvertently engineered a new form of torment. The biological mechanisms described here-NMDA receptor upregulation, dynorphin surges, metabolite neurotoxicity-are not merely pharmacological side effects; they are the body’s desperate attempt to restore equilibrium in the face of chemical intrusion. One cannot help but reflect on the paradox: we seek to quiet the nervous system, yet we amplify its noise. This is not merely a clinical dilemma-it is a philosophical one.

Just had a patient yesterday who’d been on 400mg morphine daily for 3 years. Pain was everywhere-hands, feet, scalp. Didn’t respond to anything. Cut to 150mg, switched to methadone, added gabapentin. Two weeks later? She cried because she could hug her granddaughter without screaming. OIH is real. It’s underdiagnosed. And we’re failing people by not asking the right questions. Stop assuming tolerance. Start looking for spread.

But what if you’re scared to reduce? I’ve been on opioids for 7 years and I don’t know if I can handle the pain. What if I just die from it? I need them. I need them. I need them.

i read this and cried a little. i’ve been through this. no one believed me. my dr said i was ‘too emotional’ but when i dropped my dose i could finally sleep without feeling like my bones were cracking. thank you for writing this. you saved someone today. 🌻

Let’s cut through the fluff. The entire narrative here is built on cherry-picked anecdotes and a vague understanding of neuroplasticity. If OIH were so common, why isn’t it showing up in large-scale RCTs? Why are the prevalence rates so wildly inconsistent? And why do people who ‘recover’ after tapering always seem to have perfect access to pain specialists and ketamine clinics? This isn’t science-it’s a movement disguised as medicine.

In India, many patients are given opioids without proper follow-up. We rarely screen for OIH because the infrastructure doesn’t exist. But I’ve seen it-patients on high doses of tramadol for back pain, now feeling burning in their fingers, unable to hold a cup. They are told to increase the dose. This article is not just important-it is urgent. We need global awareness, not just American clinics.

So what? People get addicted. They get greedy. This is just a fancy term for drug seeking. You don’t get to call your addiction a medical condition and expect sympathy. If you want to feel better, get off the pills. Simple.

i live in a village where the only medicine is paracetamol and prayer. but i know someone who took morphine for cancer and now she screams when the wind blows. no one knows why. thank you for naming it. maybe now someone will listen

OMG this is SO relatable 😭 I had no idea this was a thing. I thought I was just ‘broken’-now I know my body was fighting back. I’m switching to buprenorphine next week. Fingers crossed 🙏

Western medicine is a joke. We have been using Ayurvedic herbs like ashwagandha and curcumin for centuries to calm the nervous system without poisoning the body. Now you want to give ketamine infusions and switch opioids? Pathetic. Your system is broken because you trust pills over nature. We don’t need your drugs-we need your humility.

So let me get this straight… you’re telling me the solution to ‘pain from opioids’ is… more opioids? Just different ones? And you’re calling this progress? 🤡