When a generic drug hits the market, you might wonder: is it really the same as the brand-name version? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just technical terms-they’re the gatekeepers that decide whether a generic medicine is safe and effective enough to replace the original.

What Cmax and AUC Actually Measure

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It tells you how high the drug goes in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a mountain on a graph. If you take a painkiller and your blood levels spike quickly, that’s Cmax. It’s critical for drugs where timing matters-like an antibiotic that needs to hit high levels fast to kill bacteria, or a sedative where too high a peak could cause drowsiness or breathing trouble.

AUC, or area under the curve, measures the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. Imagine tracing the whole shape of the drug’s journey in your blood-from when it enters, peaks, and slowly leaves. That area? That’s AUC. It’s not just about how high you go-it’s about how long you stay there. For drugs like statins or blood thinners, total exposure matters more than the peak. If your body doesn’t absorb enough over time, the drug won’t work.

Both are measured in standard units: Cmax in mg/L or ng/mL, AUC in mg·h/L or ng·h/mL. These numbers come from drawing blood samples after a dose-usually every 15 to 60 minutes for the first few hours, then less often as the drug clears. Modern labs use liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to detect even tiny amounts, sometimes as low as 0.1 ng/mL. That precision is what makes the whole system work.

Why Both Numbers Are Non-Negotiable

Regulators don’t just look at one. They demand both Cmax and AUC pass the same strict test. Why? Because they measure different things.

Let’s say a generic drug has the same AUC as the brand-name version-that means your body gets the same total dose. But if its Cmax is 50% higher, you might get a sudden rush of drug that causes side effects. On the flip side, if Cmax is fine but AUC is 30% lower, the drug just doesn’t stick around long enough to work. Neither scenario is acceptable.

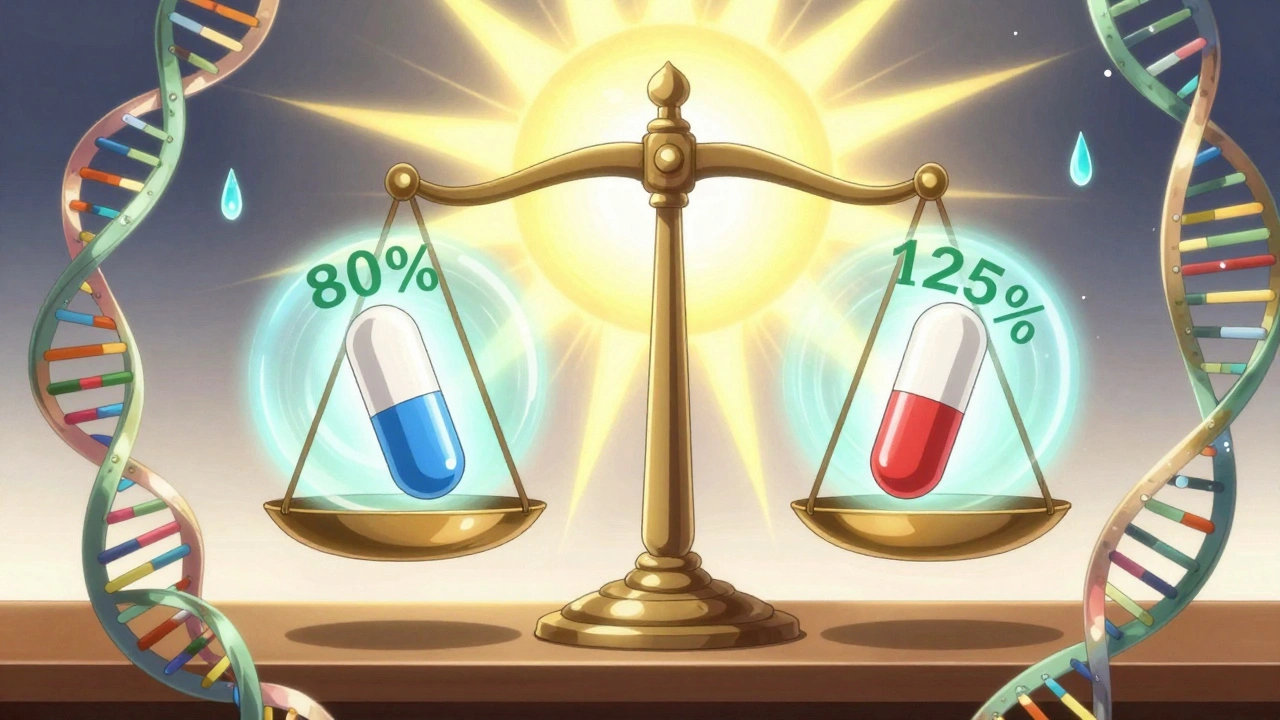

Take warfarin, a blood thinner with a narrow safety window. A tiny change in exposure can mean the difference between a clot and a bleed. That’s why regulators are extra careful. For most drugs, the rule is simple: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of generic to brand (geometric mean) must fall between 80% and 125% for both AUC and Cmax.

That 80-125% range isn’t random. It comes from decades of data and statistical modeling. On a log scale, it’s symmetrical: ln(0.8) = -0.2231, ln(1.25) = 0.2231. This accounts for the fact that drug levels in blood don’t follow a normal bell curve-they follow a log-normal distribution. Most people don’t need to know the math, but regulators do. And they won’t approve a generic unless both numbers land in that range.

How Bioequivalence Studies Work

Before a generic drug can be sold, it must pass a bioequivalence study. These aren’t done on patients-they’re done on healthy volunteers, usually 24 to 36 people. Each person gets both the brand and generic versions, in random order, with a washout period in between. This crossover design cancels out individual differences in metabolism.

Each volunteer gives blood samples-typically 12 to 18 times over 24 to 72 hours, depending on the drug’s half-life. The sampling schedule is crucial. If you miss the first hour or two, you might not catch the real Cmax. Industry data shows that poor sampling during absorption is one of the top reasons studies fail. That’s why regulators insist on actual sampling times, not just scheduled ones.

Once the data’s in, it’s transformed using logarithms (because drug levels are log-normal), then analyzed using statistical models. The ratio of geometric means is calculated for both AUC and Cmax. If both fall within 80-125%, the products are declared bioequivalent. No clinical outcome trials needed. That’s the whole point: if the body absorbs them the same way, they’ll work the same way.

Exceptions and Evolving Rules

Not all drugs fit neatly into the 80-125% box. Some, like levothyroxine or cyclosporine, have such narrow therapeutic windows that even a 10% difference matters. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) allows tighter limits-90-111%-for these. The FDA has also started allowing scaled bioequivalence for highly variable drugs (those with more than 30% variability between doses in the same person). This lets more generics pass without lowering safety standards.

Modified-release drugs are another challenge. A tablet that releases drug slowly over 12 hours doesn’t have a single peak. Its Cmax might be low, but the total exposure is still high. For these, regulators now sometimes look at partial AUC-like the area under the curve during the first 4 hours-to make sure the early release isn’t too fast or too slow.

And while modeling and simulation are being explored to reduce the need for human studies, they’re not ready to replace AUC and Cmax yet. Even in 2025, no computer model can fully replicate how real people absorb drugs. So for now, blood draws and curves are still the gold standard.

Why This Matters to You

Every time you pick up a generic pill, you’re benefiting from this system. In 2022, the U.S. FDA approved over 1,200 generic drugs-almost all relying on AUC and Cmax data. Globally, the bioequivalence testing market is worth over $2 billion and growing. And the results? A 2019 analysis of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs that passed bioequivalence testing.

That’s not luck. It’s science. The system works because it’s built on decades of research, real-world data, and strict standards. You don’t need to understand the math. But knowing that Cmax and AUC are the reason your $5 generic works just like your $50 brand name? That’s worth remembering.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence

Regulators are watching new drug types closely. Biologics, complex inhalers, transdermal patches-these don’t behave like simple pills. Their absorption is messy. But even here, AUC and Cmax are still the starting point. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance on modified-release products still lists them as primary endpoints.

One thing’s clear: no matter how advanced the tech gets, the core idea won’t change. If two products don’t deliver the same peak and the same total exposure, they’re not the same. And for patients, that’s the only thing that matters.

What does Cmax tell you about a drug?

Cmax tells you the highest concentration of a drug in your bloodstream after you take it. It shows how quickly the drug is absorbed and is especially important for drugs where high peak levels can cause side effects or where rapid action is needed, like painkillers or antibiotics.

Why is AUC more important than Cmax for some drugs?

AUC measures total drug exposure over time, so it’s more relevant for drugs that need to stay in your system for a long time to work-like statins for cholesterol or blood thinners. Even if the peak is low, if the total exposure is right, the drug will be effective.

What’s the 80-125% rule in bioequivalence?

The 80-125% rule means the ratio of the generic drug’s AUC or Cmax to the brand-name drug’s must fall between 80% and 125% for both to be considered bioequivalent. This range ensures no clinically meaningful difference in absorption, based on decades of pharmacokinetic data and statistical analysis.

Do all generic drugs need to meet the same Cmax and AUC standards?

Yes, all immediate-release generics must meet the same 80-125% criteria for both AUC and Cmax. But for drugs with very narrow therapeutic windows (like warfarin) or high variability, regulators may apply tighter limits (e.g., 90-111%) to ensure safety.

Can a generic drug pass bioequivalence testing but still not work the same in patients?

If a generic passes the official bioequivalence tests for AUC and Cmax, clinical studies show it works the same as the brand. A 2019 meta-analysis of 42 studies found no meaningful differences in effectiveness or safety. Failures are rare and usually due to manufacturing issues, not the testing system.

Why are bioequivalence studies done on healthy volunteers?

Healthy volunteers eliminate variables like disease, other medications, or organ damage that could affect how a drug is absorbed. This gives a clearer picture of how the drug itself behaves. Once bioequivalence is proven, it’s assumed to hold true across patient populations.

Cmax and AUC are the only things that matter and if you don't get why that's the gold standard you're not qualified to even discuss generics

Look I get that regulators say this is science but let's be real - the same labs that approve these generics also get paid by the pharma companies. I've seen the data dumps from FOIA requests. They fudge the sampling times. They drop outliers that don't fit the 80-125% range. And don't even get me started on how they define 'healthy volunteers' - half of them are college kids on Adderall. The system is rigged to keep prices low and profits high. You think your $5 pill is the same? It's the same chemical formula, sure. But the fillers? The coating? The dissolution profile? Totally different. And your body knows it. That's why you get weird side effects no one talks about. The FDA doesn't test for long-term outcomes. Just peak and area. That's not medicine. That's accounting.

Actually, Rachel, your concerns aren't entirely unfounded - but the regulatory framework has evolved to account for variability. The 80-125% interval isn't arbitrary; it's derived from pharmacokinetic models that account for intra- and inter-individual variation. For highly variable drugs, scaled average bioequivalence is now permitted, which allows for wider limits based on the reference drug's own variability. Also, LC-MS/MS methods can detect concentrations down to 0.01 ng/mL now - far more precise than even a decade ago. The real issue isn't fraud - it's public misunderstanding. Most people think 'bioequivalence' means 'identical,' but it means 'therapeutically equivalent' - which is a nuanced, statistically rigorous standard.

It is important to understand that bioequivalence testing is based on decades of clinical and pharmacological research. The use of healthy volunteers is standard practice to eliminate confounding variables. The 80-125% range has been validated across thousands of studies. Generics are safe and effective. This is not speculation. It is evidence-based medicine.

I’ve worked in clinical trials for over 15 years, and I can tell you that the bioequivalence process is one of the most tightly controlled parts of drug development. The sampling schedules are baked into protocols with millisecond precision - every blood draw is timestamped, logged, and audited. Labs are inspected by the FDA and EMA regularly. And the statistical models? They’re open-source now. Anyone can replicate them. The idea that this is some corporate conspiracy ignores the fact that generic manufacturers have zero incentive to cheat - if they fail, they lose millions. And if they get approved, they’re under constant surveillance. The real threat isn’t the regulators - it’s misinformation. People think they’re saving money by avoiding generics, but they’re risking their health by not taking their meds at all.

Of course it's all just math. That's why we're here - to admire the elegance of log-normal distributions and geometric means. Meanwhile, real people are dying because their blood thinners aren't working. But hey, at least the CI is within 80-125%. That's what matters, right? The math doesn't lie - but the people who run the math sure do. I'm not saying generics are bad. I'm saying the system is designed to make you believe they're perfect. And that's the real danger.

Man, I’ve sat through enough PK/PD meetings to know this stuff inside out. The 80-125% isn’t magic - it’s the point where the 90% CI crosses the equivalence boundary based on clinical relevance thresholds from decades of post-marketing data. And yeah, for warfarin? EMA’s 90-111% is way smarter. But here’s the kicker - most prescribers don’t even know what AUC stands for. That’s the real problem. We’ve got a system that works brilliantly… and a public that thinks it’s witchcraft. We need better education, not more suspicion.

Just because you can measure Cmax and AUC doesn’t mean you understand what’s happening in the gut or liver. Drug absorption isn’t just about blood levels - it’s about transporters, enzymes, gut flora. The system assumes everyone’s the same. But we’re not. My cousin took a generic statin and got rhabdo. The brand never did. The study didn’t capture that because it wasn’t statistically significant. But it happened. Real people. Real side effects. The math doesn’t see the outliers. The system doesn’t care. And that’s terrifying.

If you’re still worried about generics, you’re not alone - but you’re wrong. The data is overwhelming. Over 1,200 generics approved last year. Zero meaningful safety gaps. That’s not luck. That’s science working exactly as designed. Stop letting fear drive your choices. Your health is too important for that. Take the generic. Save money. Trust the process. And if you’re still skeptical? Talk to your pharmacist. They see this every day - and they’ll tell you the same thing: it works.

Rebecca, you’re cute. But you’re repeating the script. The FDA approved 1,200 generics - but how many were recalled? How many had manufacturing violations? How many had batch-to-batch variability that only showed up after millions of doses? You think the FDA inspects every plant? They inspect one every 18 months. And the ‘zero meaningful gaps’? That’s from studies that last 6 weeks. What about 6 months? 6 years? The system wasn’t built to catch slow-burn toxicity. It was built to approve pills fast and cheap. And now we’re all guinea pigs in the longest running experiment in medical history.