What Is Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) happens when a vein in the retina - the light-sensitive layer at the back of your eye - gets blocked. This blockage stops blood from draining properly, causing fluid and blood to leak into the retina. The result? Sudden, painless vision loss in one eye. It can be mild, like blurry spots, or severe, leaving you with almost no vision.

There are two main types: central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), which affects the main vein, and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO), which blocks smaller branches. BRVO is more common and often happens where a hardened artery presses down on a vein, like a kink in a hose. CRVO is rarer but usually more serious.

It’s not rare. About 16.4 million people worldwide have had RVO, and it’s one of the top causes of vision loss after diabetic eye disease and glaucoma. Most cases happen after age 55, but it can strike younger people too - especially those with blood disorders or who take birth control pills.

Who’s at Risk for Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Age is the biggest risk factor. Over 90% of CRVO cases occur in people over 55, and more than half of all RVO cases happen in those over 65. But don’t think you’re safe just because you’re young. About 5-10% of cases affect people under 45.

High blood pressure is the #1 medical risk. Up to 73% of CRVO patients over 50 have hypertension. Even if your blood pressure is only slightly elevated, it can damage the tiny blood vessels in your eye over time. Uncontrolled high blood pressure is especially dangerous for BRVO.

Diabetes is another major player. Around 10% of RVO patients over 50 have diabetes, and if you do, your vision recovery is often slower and less complete. High cholesterol also plays a role - 35% of RVO patients have total cholesterol above 6.5 mmol/L, regardless of age.

Glaucoma increases your risk too. High pressure inside the eye can squeeze the retinal vein, especially near the optic nerve. Smoking? It doubles your risk. Studies show 25-30% of RVO patients are current or former smokers.

For women under 45, birth control pills are a common link to CRVO. Hormones can make blood more likely to clot. Other rare but serious causes include blood cancers like multiple myeloma, polycythemia vera, and inherited clotting disorders like factor V Leiden or protein S deficiency.

Lifestyle matters. Being overweight, sitting too much, and not moving enough raise your risk. It’s not just about age - it’s about how your body handles blood flow over time. Think of it as your veins getting clogged from the inside out.

How Are RVO Injections Used to Treat Vision Loss?

There’s no way to unblock the vein once it’s closed. But you can treat the damage it causes - mainly macular edema, which is fluid buildup in the center of the retina. That’s where vision gets blurry.

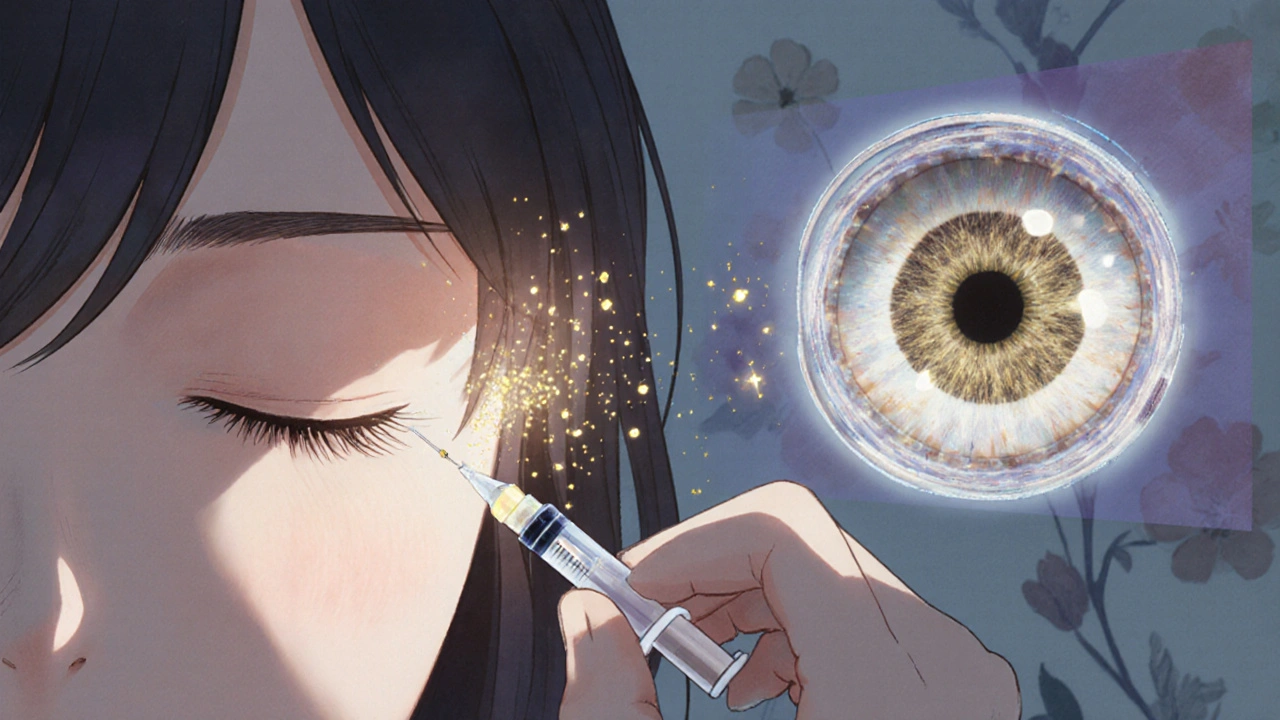

The go-to treatment? Injections into the eye. These aren’t shots you get in your arm. They’re tiny, precise injections through the white part of the eye, right into the gel-like vitreous. It’s quick - takes 5 to 7 minutes - and done under local numbing drops.

Two main types of injections are used: anti-VEGF drugs and steroid implants.

Anti-VEGF drugs - like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) - block a protein called VEGF that causes leaky blood vessels. Clinical trials show these can improve vision by 15-18 letters on an eye chart within 6 months. That’s often the difference between not reading street signs and driving again.

Steroid implants - like Ozurdex - release dexamethasone slowly over months. They’re especially helpful if anti-VEGF drugs don’t work well enough. One study found 27.7% of CRVO patients gained 15 or more letters of vision with Ozurdex, compared to just 12.9% without it.

Doctors usually start with anti-VEGF injections because they’re safer long-term. Steroids can cause cataracts in 60-70% of people who still have their natural lens, and they can raise eye pressure, sometimes requiring extra medication.

How Often Do You Need Injections?

It’s not a one-and-done fix. Most patients need monthly injections for the first 3-6 months. Then, doctors switch to a "treat-and-extend" plan: if your eye stays stable, they stretch the time between shots - maybe to every 6 weeks, then every 8, then every 12.

Real-world data shows people with RVO typically get 8-12 injections in the first year. Some need more. The goal is to keep the fluid under control. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans measure the thickness of the retina. If it’s above 300 microns, you’re likely due for another shot. Once it drops below 250 microns, you can go longer between treatments.

One recent study called COMINO showed that treat-and-extend works just as well as monthly shots - but with 30% fewer injections. That’s a big deal for people who dread going in every month.

What Are the Side Effects and Risks?

Most people tolerate injections well. But there are risks.

Common side effects include:

- A red spot on the white of the eye (subconjunctival hemorrhage) - happens in 25-30% of cases. It looks scary but clears up in days.

- Floaters - tiny dots or lines in your vision - last a few days after the shot.

- Temporary increase in eye pressure - happens in 15-20% of cases and usually goes away on its own.

Serious problems are rare but possible:

- Endophthalmitis - a severe eye infection - occurs in about 1 in 5,000 injections. That’s less than 0.1%.

- Cataracts - from steroid implants - affect most people over 50 who still have their natural lens.

- Glaucoma - from steroid-induced pressure spikes - may need lifelong eye drops.

Most patients say the fear of the injection is worse than the actual experience. The needle is tiny. The numbing drops work fast. And doctors do hundreds of these a year.

Cost, Access, and Real Patient Experiences

The cost of treatment varies wildly. In the U.S., a single dose of Lucentis or Eylea costs around $2,000. Avastin, which is used off-label, costs about $50. Because of this, many safety-net clinics use Avastin - it’s just as effective for most people.

But insurance doesn’t always cover it the same way. Some patients pay $150 per injection out-of-pocket. After 10 shots, that’s $1,500 - not easy on a fixed income.

One patient on a support forum wrote: "I got 8 Avastin shots with no improvement. Then I got Ozurdex - my vision jumped 10 lines. Worth every penny." Another said: "I miss appointments because I get so anxious before each shot. My vision keeps getting better, but I can’t face the fear anymore."

Surveys show 78% of RVO patients see real vision improvement after a year of treatment. But 63% say the cost is a burden, and 41% feel exhausted by the treatment schedule. That’s why newer options - like a slow-release implant that lasts 6 months - are being tested.

What’s Next in RVO Treatment?

The future is about less frequent treatment and smarter targeting.

Gene therapy is in early trials. One approach, RGX-314, aims to give your eye the ability to make its own anti-VEGF protein - potentially eliminating the need for injections altogether.

Another drug, OPT-302, blocks a different VEGF protein and is being tested alongside Eylea for patients who don’t respond well to standard therapy.

And there’s the Port Delivery System - a tiny refillable implant placed in the eye that slowly releases Lucentis. It’s already approved for another eye disease and is now being tested for RVO. If it works, patients might only need refills every 6 months instead of monthly shots.

Doctors are also using new imaging tools to predict who will respond best to which treatment. Some patients respond better to steroids from the start. Others need anti-VEGF. Personalized treatment is no longer a dream - it’s happening now.

What Should You Do If You Have RVO?

First, get diagnosed properly. That means an eye exam, OCT scan, and sometimes a dye test called fluorescein angiography. Don’t delay - early treatment gives you the best chance to save vision.

Second, control your risk factors. Take your blood pressure meds. Lower your cholesterol. Quit smoking. Manage your diabetes. These aren’t optional. They’re part of your eye treatment plan.

Third, stick with the injections. Yes, they’re annoying. Yes, they’re expensive. But skipping them means your vision will likely get worse - and faster than you think.

Finally, talk to your doctor. Ask about your options. If monthly shots are too much, ask about treat-and-extend. If cost is a problem, ask about Avastin. If your vision isn’t improving, ask about switching to a steroid implant. You have choices. Use them.

I've seen this happen to my uncle. He thought it was just a bad day until he couldn't read his own name on the mailbox. Now he gets injections every 6 weeks and swears by Avastin. Cost? $50. Insurance? Didn't care. Vision? Back to driving. Don't let fear or price stop you - your eyes don't negotiate.

Big pharma loves these injections because they make you dependent. Why not fix the root cause? Your blood is toxic from processed food and vaccines. They dont tell you that. 90% of these cases are from GMO corn syrup and 5G towers messing with your capillaries. I know because I read a blog once

In India, we call this 'netri roga' - the eye's rebellion against a life lived too fast. My grandmother had it. She never saw a doctor, but she drank neem water, rubbed her eyes with turmeric paste, and prayed to Dhanvantari. She lost vision in one eye… but kept her peace. Modern medicine fights the symptom. Ancient wisdom heals the soul. Maybe both are needed.

The clinical data supporting anti-VEGF therapy is robust, with randomized controlled trials demonstrating statistically significant improvements in best-corrected visual acuity. However, the long-term safety profile of repeated intravitreal injections remains incompletely characterized, particularly regarding the potential for retinal atrophy and chronic inflammation. The economic burden, while mitigated by off-label use of bevacizumab, introduces systemic inequities in access.

ok so i got the avastin shot and nothing happened then i got the ozurdex and my vision went from blurry to like i could read the fine print on a pill bottle?? like wtf?? also why is everyone so scared of the needle?? it's like a mosquito but with more drama

Nigeria has zero access to these injections. We have one ophthalmologist per 500,000 people. Meanwhile, Americans are debating whether to use Eylea or Lucentis. This isn't healthcare - it's a luxury sport. If your eye is dying, you better be rich. And don't even get me started on how they charge $2000 for a shot that costs $5 to make.

They say it's about blood pressure and cholesterol. But let’s be real - it’s the sugar. The processed sugar. The high-fructose corn syrup in everything. The food industry is poisoning us and then selling us the cure. And you think you’re safe because you don’t smoke? Wake up. Your soda is your enemy.

I used to hate going in for injections. Felt like a lab rat. Then I realized - I’m not just getting a shot. I’m buying back my life. I can see my granddaughter’s face now. I can read her bedtime stories. That’s worth 12 shots. And yes, the red spot looks like a crime scene. But it fades. So does the fear.

If you're reading this and you're scared of the injections - you're not alone. I was too. But my doctor sat with me for 20 minutes before the first one. She didn't rush. She listened. That made all the difference. You deserve care that sees you as a person, not a case number.

The utilization of off-label bevacizumab represents a significant ethical and regulatory dilemma. While cost-effective, its non-FDA-approved status for intravitreal administration introduces liability concerns for providers and potential risks for patients due to compounding inconsistencies. Regulatory agencies must address this gap to ensure equitable and standardized care.

I'm a retinal nurse in London - we use the treat-and-extend protocol religiously. Patient compliance skyrockets when they realize they don't need to come every month. One guy went from 12 shots a year to 5. He cried. Said he finally felt like he had his life back. That’s the real win.

The data is clear: steroid implants increase intraocular pressure in 30-40% of cases. This is not a minor side effect - it's a gateway to permanent glaucoma. Why are we still using them as first-line? The FDA should require stronger warnings. And Avastin? It's not 'just as effective' - it's the only responsible choice.

I had BRVO. Got 11 injections. Now my vision is 20/25. I still get OCT scans every 3 months. I don't panic anymore. I just show up.

So I skipped my last shot because I was 'too tired'. Two weeks later, I couldn't see the coffee cup in front of me. Yeah. Lesson learned. You don't get to choose when your eyes take a break. They don't care if you're 'over it'.