Most people think obesity is just about eating too much and moving too little. But that’s not the full story. Under the surface, your body’s hunger signals, metabolism, and brain wiring are all out of sync. This isn’t laziness or lack of willpower-it’s a biological malfunction. The science behind it is complex, but the bottom line is simple: obesity is a chronic disease of energy regulation gone wrong.

How Your Brain Controls Hunger

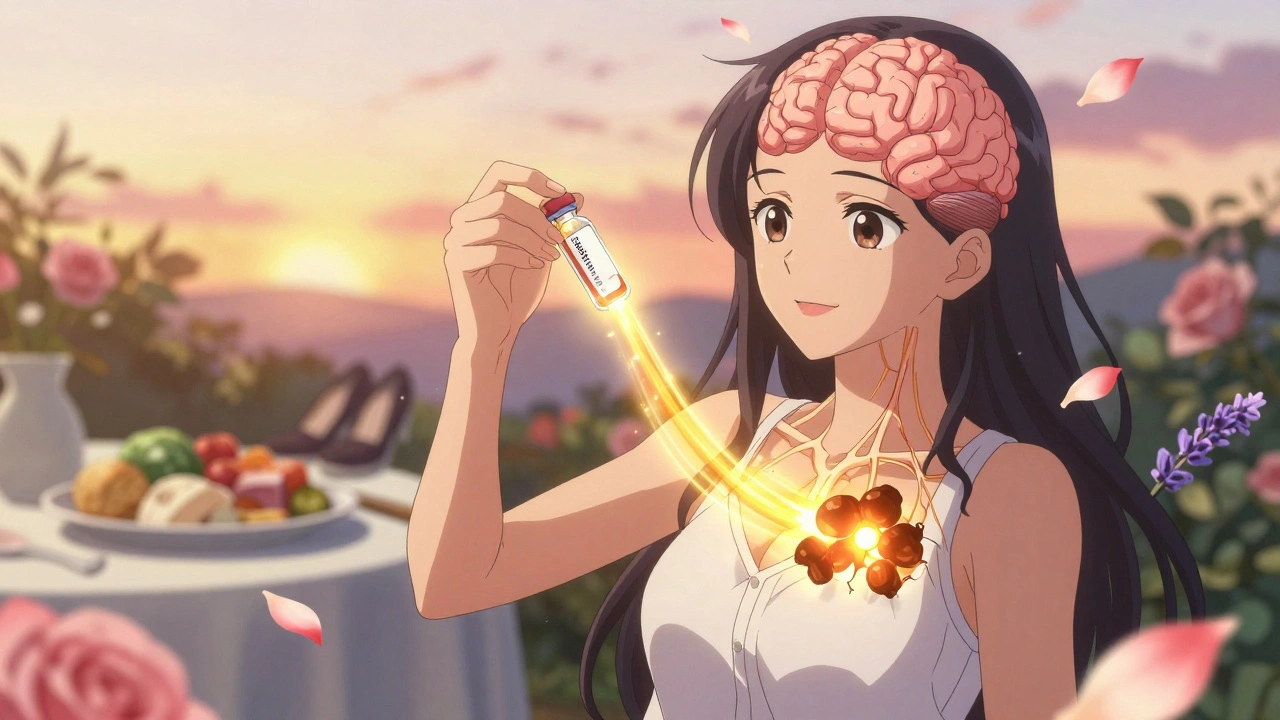

Deep inside your hypothalamus, a tiny region of your brain acts like a thermostat for your body weight. Two opposing groups of neurons keep your energy balance in check. One group, called POMC neurons, tells you to stop eating. They release a chemical called alpha-MSH, which activates receptors that make you feel full. In lab studies, turning on these neurons cuts food intake by 25 to 40%. The other group, made up of NPY and AgRP neurons, screams for food. When activated, they can make a mouse eat 300 to 500% more in minutes. These aren’t just abstract cells-they’re the real drivers of your cravings.These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to signals from your fat cells, gut, and pancreas. Leptin, a hormone made by fat tissue, tells your brain, “I’ve got enough stored.” In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, they jump to 30-60 ng/mL. But here’s the catch: your brain stops listening. This is called leptin resistance, and it’s the core problem in most cases of obesity. Your body is drowning in leptin, but your hunger centers don’t hear it. So you keep eating, even when you’re full.

The Hormones That Trick Your Brain

Leptin isn’t the only player. Insulin, which rises after meals, also tells your brain to reduce appetite. But in obesity, insulin signaling in the brain gets fuzzy too. Ghrelin, the “hunger hormone,” does the opposite. It spikes right before meals-from 100-200 pg/mL when you’re fasting to 800-1000 pg/mL when you’re about to eat. In obese individuals, ghrelin doesn’t drop properly after meals, so hunger lingers. Then there’s pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after eating to slow digestion and curb appetite. Studies show 60% of people with diet-induced obesity have abnormally low PP levels. Their bodies don’t send the “I’m done” signal effectively.Even hormones like estrogen play a role. After menopause, women often gain belly fat. That’s because estrogen helps regulate both appetite and energy use. When estrogen drops, women eat more and burn fewer calories. Experiments with mice lacking estrogen receptors show a 25% increase in food intake and a 30% drop in energy expenditure. It’s not just about calories-it’s about how your body uses them.

Why Your Body Resists Weight Loss

Losing weight isn’t just hard-it’s biologically opposed. When you lose fat, your fat cells shrink and produce less leptin. Your brain interprets this as starvation. It ramps up hunger signals, slows your metabolism, and makes food more rewarding. This isn’t psychological-it’s evolutionary. Your body is trying to protect you from famine. That’s why most people regain weight after dieting. The system is designed to hold onto fat, not lose it.Another layer is the brain’s reward system. Highly processed, sugary, fatty foods hijack the same circuits that evolved for survival. When you eat them, dopamine surges, reinforcing the behavior. In people with leptin resistance, the melanocortin system-which normally limits reward-driven eating-doesn’t work well. That means you’re not just hungry; you’re driven to eat pleasurable foods, even when you’re not physically in need of calories.

Metabolic Dysfunction: More Than Just Fat Storage

Obesity isn’t just about excess fat. It’s about how that fat changes your entire metabolism. Fat tissue in obese individuals becomes inflamed and dysfunctional. It releases chemicals that interfere with insulin action, leading to insulin resistance. That’s the gateway to type 2 diabetes. But it’s not just the liver and muscles that suffer. Your brown fat, the kind that burns calories to make heat, becomes less active. In lean people, brown fat helps burn 200-300 extra calories a day. In obesity, that system shuts down.Signaling pathways inside brain cells also break down. The PI3K-AKT pathway, which lets leptin and insulin tell your brain to stop eating, becomes less responsive. When scientists blocked this pathway in mice, leptin lost its ability to reduce food intake. Another pathway, involving JNK, gets overactivated in obesity and makes brain cells resistant to leptin. Even mTOR, a nutrient-sensing system, gets dysregulated. Stimulating it reduces appetite in mice-but in humans, it’s unclear how to safely target it.

What Treatments Actually Work?

Traditional diets fail because they don’t fix the biology. But new drugs are starting to. Setmelanotide, a drug that activates the melanocortin-4 receptor, works wonders in rare genetic forms of obesity. In people with POMC or LEPR mutations, it cuts weight by 15-25%. But it’s not for everyone.More broadly, semaglutide-a GLP-1 receptor agonist-has changed the game. It slows digestion, reduces appetite, and boosts fullness. In clinical trials, people lost an average of 15% of their body weight. It works because it taps into multiple appetite pathways at once. Other drugs in development target ghrelin, serotonin, or orexin systems. One exciting 2022 discovery found a group of neurons next to hunger and satiety cells that, when activated, shut down eating within two minutes. That could lead to entirely new therapies.

But drugs aren’t magic. They work best when combined with lifestyle changes. The goal isn’t to “fix” your willpower-it’s to support your biology. If your brain is screaming for food, no amount of discipline will win that battle alone.

Why This Matters for Everyone

Obesity affects 42.4% of U.S. adults and nearly 13% of the global population. That’s over 900 million people. It’s linked to 2.8 million deaths a year and costs the U.S. healthcare system $173 billion annually. Yet, we still treat it like a personal failure. Understanding the biology changes everything. It means we stop blaming people and start treating the disease.For those struggling with weight, this isn’t about eating less. It’s about resetting a broken system. For doctors, it means moving beyond “eat less, move more.” For researchers, it means developing therapies that restore the body’s natural balance-not suppress it.

The science is clear: obesity is not a choice. It’s a complex, deeply rooted disorder of appetite and metabolism. And until we treat it as such, we’ll keep failing the people who need help the most.

Is obesity caused by eating too much?

No, not in the way most people think. While overeating plays a role, the real issue is a biological malfunction. Hormones like leptin and ghrelin send faulty signals to the brain. Your body doesn’t recognize when it’s full, and your metabolism slows down to conserve energy. This isn’t about willpower-it’s about a system that’s been rewired by genetics, environment, and chronic inflammation.

Why do diets rarely work long-term?

When you lose weight, your fat cells shrink and produce less leptin. Your brain interprets this as starvation and responds by increasing hunger, reducing energy expenditure, and making food more rewarding. This is a survival mechanism that evolved to prevent famine. Most diets ignore this biology, which is why 80-90% of people regain the weight within two years.

What is leptin resistance?

Leptin resistance is when your brain stops responding to the hormone leptin, even though your fat cells are producing high levels of it. Normally, leptin tells your brain you have enough energy stored. In leptin resistance, that signal gets ignored. This leads to constant hunger and reduced calorie burning. It’s the main reason why obesity is so hard to reverse without medical intervention.

Do genetics play a role in obesity?

Yes, but not in the way most people assume. While rare genetic mutations (like in the leptin or MC4R genes) can cause severe obesity, they affect fewer than 50 people worldwide. Most cases are due to a combination of common gene variants that make people more sensitive to environmental triggers-like processed foods, lack of sleep, or stress. These genes don’t cause obesity alone, but they make it far more likely when combined with modern lifestyles.

Are weight-loss drugs like semaglutide safe?

Semaglutide and similar drugs are FDA-approved and have been tested in tens of thousands of people. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, especially when starting. These usually improve over time. Long-term safety data is still being collected, but so far, the benefits outweigh the risks for people with obesity and related conditions like type 2 diabetes. They’re not for casual use-they’re designed for people with a medical diagnosis of obesity.

Can you reverse metabolic dysfunction from obesity?

Yes, but it takes time and sustained effort. Losing just 5-10% of body weight can improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and lower liver fat. Some people on long-term GLP-1 agonists see their metabolic markers return to near-normal levels. The key is consistency-not perfection. Your body doesn’t reset overnight, but with the right support, many of these changes can be reversed.

Finally, someone says it like it is. This isn't about willpower-it's biology. I've been fighting my body for years, and no amount of gym memberships or salad bowls fixed what was broken inside. The science here? It's real. And it's personal.

For anyone who's ever been told to 'just eat less,' know this: your brain is literally screaming at you to eat more. It's not laziness. It's a system glitch. And we need to treat it like one.

Ugh. I hate when people act like obesity is just a ‘lifestyle choice.’ My mom had bariatric surgery and still gets judged at the grocery store. Like she’s some kind of failure. She’s not. Her brain just stopped listening to her fat cells. And now she’s stuck paying for it with shame.

Also, why do people think losing weight is like turning off a light switch? It’s not. It’s like trying to unplug a house that’s wired wrong.

While the biochemical mechanisms described are empirically valid, one must interrogate the ontological presuppositions embedded within the discourse of ‘disease.’ The medicalization of adiposity, while ostensibly liberating, inadvertently reinforces a biopolitical regime wherein the body is rendered legible only through pathological frameworks. Leptin resistance, though measurable, is not an ‘error’-it is an adaptive response to an industrialized food environment. To pathologize is to depoliticize. The real malfunction is not in the hypothalamus-it is in the capitalist alimentary apparatus.

Bro. This is the most accurate thing I’ve read all year. 🤯

Leptin resistance? Yeah. I felt like my brain was on a loop: ‘eat more’ → ‘you’re full’ → ‘nope, eat more’ → ‘why am I still hungry?!’

And don’t even get me started on how junk food hijacks your dopamine like a hacker with a backdoor. I used to think I was weak. Turns out, my neurons were just being manipulated by sugar-coated corporate algorithms. 😅

Semaglutide? I’m not on it, but I’m not judging people who are. If your brain’s broken, why not fix it? No shame in using tools. We use glasses for bad eyesight-why not meds for bad hunger signals?

This is so important. Stop blaming people.

Oh wow. So now it’s not my fault I gained 60 pounds after my divorce? My brain just ‘stopped listening’? How convenient. Next you’ll tell me my cat’s meowing is due to ‘neurochemical dysregulation.’

Meanwhile, my neighbor lost 100 lbs on a keto diet and runs marathons. Maybe it’s not all biology. Maybe it’s just… effort?

US healthcare is a joke. I paid $12,000 out of pocket for my GLP-1 script because insurance called it ‘cosmetic.’ Meanwhile, my cousin got a $500,000 liver transplant for alcoholism. Guess which one’s ‘real’ disease? 🤡

Obesity = weakness. Alcoholism = tragedy. Makes perfect sense. 😒

India also has this problem now. Fast food, stress, no sleep. Same science. Same pain. No blame. Just need better access to care. 🙏

The pathophysiological cascade is unequivocally driven by hyperpalatable food-induced endocrine disruption, compounded by epigenetic modulation of hypothalamic neuropeptide expression. The metabolic inflexibility observed is a direct consequence of chronic caloric surplus activating inflammatory cascades via TLR4/NF-κB signaling, which subsequently induces central insulin and leptin resistance. Ergo, behavioral interventions are insufficient without pharmacologic modulation of the melanocortin axis.

man this is so true i used to think i was lazy but after reading this i realized my body was just broken. i started on semaglutide last year and yeah its not magic but it helped my brain chill out. now i eat less not because i want to but because i dont feel like screaming for food all the time. thank you for writing this

While the biochemical model presented is compelling, it remains fundamentally reductionist. The notion that obesity is solely a disorder of energy regulation ignores the sociocultural architecture of food access, economic inequality, and systemic food deserts that disproportionately affect marginalized communities. To frame this as a neurological malfunction is to absolve the food industry, agricultural policy, and urban planning of their culpability. Leptin resistance may be real-but so is the fact that 80% of low-income neighborhoods lack fresh produce, while fast food outlets outnumber grocery stores 3:1. Your hypothalamus doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It operates in a world where the cheapest, most accessible calories are engineered to override satiety. The real disease isn’t in the brain-it’s in the system that profits from it. Until we address that, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic while the industry writes the textbooks.