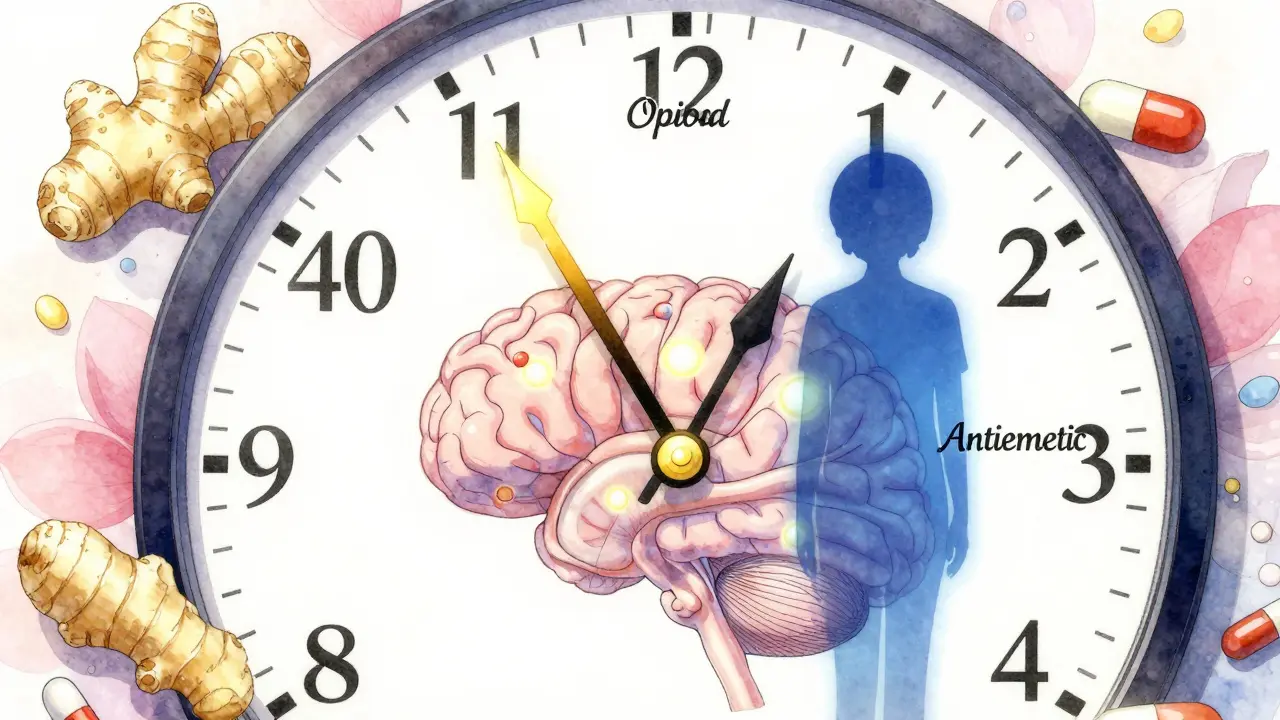

Opioid Nausea Management Calculator

Personalized Nausea Management Plan

Recommended Antiemetic

Optimal Timing Strategy

Dietary Adjustments

Opioid Switch Consideration

When you start taking opioids for pain, nausea isn’t just a nuisance-it can make you quit the medication altogether. About one in three people who begin opioid therapy feel sick to their stomach, and for many, it’s worse than the pain they’re trying to treat. This isn’t weakness or bad luck. It’s biology. Opioids trigger nausea by activating receptors in the brainstem, the same area that controls vomiting. The good news? You don’t have to suffer through it. With the right timing, the right drugs, and a few simple diet tweaks, most people get through this phase without stopping their pain treatment.

Why Opioids Make You Nauseous

Opioids like morphine, oxycodone, and hydrocodone don’t just block pain signals. They also bind to receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), a small area in your brainstem that acts like a poison alarm. When opioids activate this zone, your body thinks something toxic is in your system-and it tries to get rid of it. That’s why nausea and vomiting happen, even if you haven’t eaten anything bad.

This reaction hits hardest in the first 24 to 48 hours after starting an opioid or increasing the dose. Most people build tolerance within 3 to 7 days. But if you’re older, have cancer, or are taking other medications that affect your liver, the nausea can stick around longer. That’s why managing it early matters. Waiting until you’re throwing up every few hours means you’re already at risk of dehydration, poor nutrition, and giving up on pain control.

First-Line Antiemetics That Actually Work

Not all anti-nausea drugs are created equal when it comes to opioid-induced nausea. The most effective ones target the dopamine receptors in the CTZ. Here’s what works best, based on clinical evidence:

- Haloperidol (0.5-2 mg daily): A low-dose antipsychotic that’s cheap, effective, and often used in hospice care. It works quickly and costs less than 5 cents per tablet. But it can cause stiffness or tremors in older adults, so it’s not ideal for people over 65 unless carefully monitored.

- Prochlorperazine (5-10 mg every 6-8 hours): A phenothiazine that’s been used for decades. It’s gentler on the body than haloperidol and works well for most people. Often prescribed as a pill or suppository.

- Metoclopramide (5-10 mg every 6-8 hours): This drug doesn’t just calm the brain-it speeds up your stomach. That’s helpful if nausea is tied to slow digestion or constipation, which often go hand-in-hand with opioids. But it can cause muscle spasms or restlessness in about 10% of users, especially at higher doses.

Drugs like ondansetron (Zofran), which work on serotonin receptors, are commonly used for chemo nausea-but they’re less reliable for opioid-induced nausea. Studies show they help about half the time, compared to 70% or more with dopamine blockers. And they’re expensive. A single 4 mg Zofran tablet can cost over $3, while generic haloperidol is pennies.

When to Take Antiemetics for Maximum Effect

Timing isn’t just helpful-it’s critical. Opioids reach their peak concentration in your blood about 60 to 90 minutes after you swallow them. That’s when nausea hits hardest. If you take your antiemetic at the same time as your opioid, you’re too late.

The smart move: take your antiemetic 30 to 60 minutes before your opioid dose. That way, the anti-nausea drug is already in your system, at full strength, when the opioid starts triggering the brain’s vomiting center. For example, if you take oxycodone at 8 a.m., take prochlorperazine at 7:15 a.m. This simple trick can cut nausea by up to 50% in opioid-naïve patients.

Some doctors recommend keeping antiemetics on a fixed schedule for the first 5 to 7 days, even if you don’t feel nauseous. That’s because nausea can sneak up on you before you notice it. Once you’ve been on the same opioid dose for a week without nausea, you can stop the antiemetic. Most people develop tolerance by then.

Diet Adjustments That Reduce Nausea

What you eat-and when-can make a big difference. Opioids slow down your gut, which leads to bloating, constipation, and delayed stomach emptying. All of that makes nausea worse.

- Eat small, frequent meals. Instead of three big meals, try five or six smaller ones. A large plate of food sits in your stomach longer, increasing pressure and triggering nausea.

- Avoid greasy, spicy, or overly sweet foods. These are harder to digest and can irritate your stomach further. Stick to bland, dry foods like toast, crackers, rice, or boiled potatoes.

- Drink fluids between meals, not with them. Drinking while eating fills your stomach faster and slows digestion. Sip water, ginger tea, or clear broths an hour before or after eating.

- Try ginger. Studies show that 1 gram of powdered ginger taken 30 minutes before meals can reduce nausea in people on opioids. Ginger capsules or tea are easy to find and have almost no side effects.

- Don’t lie down after eating. Stay upright for at least 30 minutes after a meal. Gravity helps keep food moving and reduces reflux, which can worsen nausea.

One overlooked tip: if you’re constipated-which most opioid users are-treating that can ease nausea too. Constipation slows your whole digestive system, making you feel fuller and sicker. A stool softener like docusate sodium, plus plenty of water and fiber, can help. Some patients report that once their bowels move regularly, their nausea improves significantly.

When to Consider Switching Opioids

If nausea doesn’t improve after a week of antiemetics and diet changes, switching opioids might help. Not all opioids cause the same level of nausea. Some people react badly to morphine but tolerate oxycodone just fine. Others find that methadone or hydromorphone is easier on their stomach.

Here’s what the data shows:

- Switching from morphine to oxycodone reduces nausea in about 30% of patients.

- Switching to hydromorphone helps 40-50% of people, according to updated NCCN guidelines from 2023.

- Methadone is more complex to switch to-it requires careful dosing by a specialist-but can be very effective for those with persistent nausea and pain.

Don’t switch on your own. This needs medical supervision. But if your doctor hasn’t mentioned it, ask. It’s a legitimate option, not a last resort.

What Doesn’t Work (and Why)

Many people try over-the-counter remedies like Pepto-Bismol or antacids. These might help with heartburn or indigestion, but they don’t touch the brainstem trigger that opioids activate. They won’t stop opioid-induced nausea.

Prophylactic antiemetics-taking them before you even feel sick-have been studied in dozens of trials. The results? Mostly disappointing. In one meta-analysis of 619 patients, dopamine blockers like haloperidol didn’t prevent nausea when taken before opioid initiation. That means waiting until you’re nauseous to start treatment is often more effective than trying to prevent it.

And don’t assume that stronger opioids mean worse nausea. The dose matters more than the type. Starting too high is the #1 mistake. That’s why the “start low, go slow” approach works so well: beginning at 25-50% of the usual starting dose cuts nausea risk by 35-40%.

What to Do If Nausea Won’t Go Away

For 1 in 3 people, nausea lasts longer than a week. If you’ve tried antiemetics, diet changes, and timing adjustments-and you’re still sick-you’re not alone. About 42% of cancer patients stop opioids because of uncontrolled nausea, even with treatment.

At this point, you need a new plan:

- Re-evaluate your opioid dose. Sometimes, reducing it by 25-33% still gives you good pain control-and eliminates nausea entirely.

- Check for other causes. Is it your other medications? Dehydration? Anxiety? Constipation? A urinary tract infection? Nausea can have multiple triggers.

- Ask about dexamethasone. This steroid, given in low doses (4-8 mg), helps some patients, even though we don’t fully understand why.

- Consider non-drug options. Acupuncture, acupressure wristbands, or guided breathing exercises have shown promise in small studies for reducing opioid nausea.

If you’re still struggling, ask to be referred to a palliative care specialist. They see this every day. They know which combinations work, which opioids to avoid, and how to adjust doses safely. You don’t have to suffer in silence.

Final Thoughts

Nausea from opioids is common, but it’s not inevitable. You don’t have to choose between pain relief and feeling sick. With the right antiemetic, taken at the right time, combined with simple diet changes, most people get through the first week without quitting their medication. And if it doesn’t improve? There are still options-switching opioids, lowering the dose, or adding support from a specialist.

This isn’t about being tough. It’s about being smart. The goal isn’t to tolerate nausea. It’s to manage it-so you can live with your pain, not be ruled by it.

How long does opioid-induced nausea usually last?

For most people, nausea from opioids lasts 3 to 7 days after starting or increasing the dose. This is because the brain gradually adjusts to the drug. If nausea continues beyond a week despite antiemetics and diet changes, it’s time to reassess your treatment plan with your doctor.

Can I take ginger with my opioid medication?

Yes, ginger is safe to take with opioids and may help reduce nausea. Studies show that 1 gram of powdered ginger taken 30 minutes before meals can lower nausea levels. It’s available as capsules, tea, or chewable tablets. No major interactions have been reported, but always check with your pharmacist if you’re on multiple medications.

Is ondansetron (Zofran) effective for opioid nausea?

Ondansetron works moderately well for opioid-induced nausea, but it’s less effective than dopamine blockers like haloperidol or prochlorperazine. It’s often used when other drugs aren’t tolerated, but don’t expect it to work as well as first-line options. It’s also significantly more expensive.

Why does my nausea get worse after eating?

Opioids slow down digestion, so food stays in your stomach longer. Eating triggers stomach contractions, which can feel like nausea when your gut is sluggish. Eating small, bland meals and avoiding liquids during meals helps. Also, treating constipation can improve this, since a backed-up colon can press on your stomach and worsen the feeling.

Should I stop my opioid if I’m nauseous?

No-don’t stop without talking to your doctor. Nausea often improves within a week. Stopping your opioid may mean your pain returns worse than before. Instead, adjust your antiemetic, timing, or diet. If those don’t help, ask about switching to a different opioid. Quitting opioids because of nausea is common, but it’s usually avoidable with the right support.

Opioid nausea is one of those things no one talks about until you’re bent over the toilet at 3 a.m. wondering if you made a terrible life choice. It’s not weakness. It’s just biology screaming at you. I started on oxycodone after surgery and thought I was dying. Turns out, I just needed to take prochlorperazine 45 minutes before the pill. Game changer. No more vomiting, just quiet pain relief.

Wait-so Zofran doesn’t work well for opioid nausea? I’ve been taking it for weeks. My doctor said it was the gold standard. This is wild. I’m switching to haloperidol tomorrow. If it works, I’m writing a letter to my prescriber. Also, why is everyone so quiet about how much cheaper haloperidol is? Like, $0.05 vs $3? That’s insane.

Actually in India we call this 'darr ka dard'-fear pain. People think if you feel sick on opioids you are weak. But no. It’s the brainstem. The CTZ. The poison alarm. I have seen patients stop pain meds because they think it’s their fault. But it’s not. It’s biology. Ginger helps. Small meals. Don’t lie down. And if you’re constipated? Fix that first. Bowel is connected to nausea. Always.

I’m so glad someone wrote this. I was on methadone for chronic pain and felt like garbage for three weeks. My doctor didn’t mention any of this. I tried everything-Pepto, ginger tea, crackers. Nothing worked. Then I switched to hydromorphone and added prochlorperazine before each dose. Within 48 hours, I could eat without crying. Please, if you’re suffering, don’t suffer in silence. Ask for help. There’s a solution.

So you’re telling me I don’t need to take antiemetics before I even feel sick? I’ve been doing that for a month. My doc said prophylactic was best. But now I’m confused. Do I just wait until I’m nauseous? And what about the constipation? I’m taking laxatives but still feel bloated. Is that making the nausea worse?

OMG YES. Ginger tea + crackers + sitting upright after eating = my only survival tactics. I used to cry every time I took my pain meds. Now I take my haloperidol 45 min before, sip ginger tea, and just… breathe. Also, I started using a heating pad on my belly. Not science, but it helps. 🙏

You people are overcomplicating this. It’s simple: stop taking opioids if they make you sick. There are other pain options. CBD. Acupuncture. Physical therapy. Why are you clinging to something that makes you vomit? You’re not brave. You’re addicted. The brainstem isn’t your enemy. Your dependency is. Fix the root cause. Not the symptom.

Just took haloperidol 1mg before my oxycodone. 2 hours later I feel like a zombie but no nausea. Also my constipation got worse so I’m taking docusate now. The timing thing actually works. My doctor never told me this. I’m glad I found this thread. Thanks for the info. Also I’m 52 and I didn’t get tremors. Maybe I’m lucky.